The Legacy of “Mother” Lee

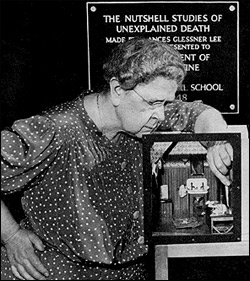

F rances Glessner Lee was credited with many distinguished honors during her eighty-five years, including her role as creator of Harvard’s department of legal medicine; donor of more than a thousand books to the George Burgess Magrath Library of Legal Medicine; namesake of the Frances G. Lee Chair in Legal Medicine; and founder the Harvard Seminars in Homicide Investigation. She is honored as the founder of the Harvard Associated in Police Science (HAPS).1

She was the first female police captain of New Hampshire state police and the first woman to be invited into the International Association for Chiefs of Police.2

Humbly, she often referred to herself as a “hobbyist.” It would be easy to pigeonhole her as the stereotypical rich eccentric indulging in a twisted compulsion to play with and murder dolls.

However, the men she taught believed otherwise. “Mrs. Lee was unquestionably one of the world’s most astute criminologists. She was acquainted with and respected by top criminologists all over the world.”3

Frances Glessner Lee died in 1962. The Harvard Department of Legal Medicine closed in 1967 for financial reasons. The then-Chief Medical Examiner of Maryland arranged for the Nutshell Studies to be moved to Baltimore where they are on permanent loan.

The Nutshells were restored in 1992 for $50,000 and are still used during the twice-yearly HAPS seminars to train investigators from around the country. They are not accessible to the public.

The Medical Examiner System

Coroners, with few exceptions, are elected lay persons who rely on other medical personnel to assist in investigations and perform autopsies. Medical examiners are usually physicians and pathologists who are appointed and have been trained in medico-legal death investigation and forensic autopsies.4

“It’s not necessary for him [the coroner] to know a tibia from a tuba, a choked drain from a choked windpipe. The only skilled knowledge he may have is how to play ball with the local political bosses.”5

Because coroners are elected, they can hold any profession—plumbers, barbers, undertakers, lawyers. Beginning in 1877 and riding the wave of medical professionalism, certain doctors began a movement to replace the coroner with the highly trained medical examiner. Massachusetts, and by extension Harvard University, seemed to be at the forefront of this movement.6

Harvard medical professors were vocal supporters of this push toward professionally trained medical examiners. Beginning in 1877, F.W Draper, a Harvard professor and president of the Massachussetts Medico-Legal Society, taught Harvard’s first course on the subject. Frances’ endowment in the 1930s codified this move at Harvard with an entire department. The first and second deparment chairs, George Burgess Magrath and Dr. Alan Moritz, respectively, were vocal supporters as well. Frances Glessner Lee and her Nutshell Studies became intertwined with this movement.7

Her program at Harvard to train medical examiners, coupled with her HAPS seminars, which focused on training the investigators and the seminars’ prominent use of the models seemed appropriately timed to illuminate the importance of the proper handling of medical evidence.

Nutshells and the ‘CSI Effect’

It’s hard to imagine a time when doctors and law enforcement had to fight for the use of forensics and pathology. We live in a world where anyone can become an amateur sleuth, just by watching television or reading any one of a plethora of mystery novels.

Many popular television dramas gain incredible ratings by focusing on the use of science and technology in crime investigations. CSI: Crime Scene Investigation has been called “the most popular television show in the world” and has spun off countless television shows focusing on the same subject matter.8 As such, millions of people are now obliquely informed of forensics and its uses, a fact which has its own pros and cons.

Perhaps another result of the CSI Effect, the Nutshell Studies have seen a resurgence of interest in American popular culture. Our national obsession with forensics is the topic of a recently-filmed documentary which prominently highlights the Nutshells, and photographer Corinne May Botz produced a coffee table book which includes all eighteen of the Nutshells and essays from her own research and family interviews.

Additionally, Thomas Mauriello, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Maryland, College Park teaches his students with his own custom-made dioramas.10

“Although few people today, even in forensic science, know about Frances Glessner Lee, her legacy lives on in those who teach via diorama, and even in a series of CSI episodes that used miniature crime scenes as clues in a serial killer investigation.”11

In our high-tech world of luminol, DNA, computer modeling and CSI, these dioramas may seem like a very low-tech option. Yet, the fact that a modern teacher of criminal justice opts to use his own speaks volumes about her legacy.