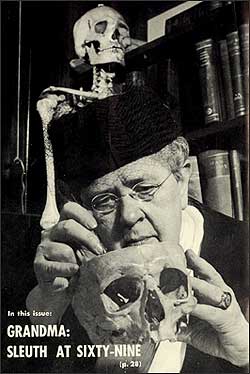

“Mother” Lee

F rances Glessner Lee was born in 1878 to John Jacob Glessner and Frances M. Glessner in Chicago, Illinois. John J. Glessner was vice president of International Harvester and as such, young “Fanny” was born into a life of Gilded Age luxury. She and her brother, George, grew up on fashionable Prairie Street in Chicago and were raised in a house that “epitomized the aesthetic and moral ideals of nineteenth-century domesticity.”1

Little has been written about her early life; except that she was educated at home by private tutors and that she learned the domestic arts of interior design, metalwork, sewing, knitting, crocheting, embroidery, and painting from her female relatives.2

She had aspired to study law or medicine, but her parents, who believed that “a lady didn’t go to school,” refused to allow her to attend a university. Instead, she married up-and-coming attorney Blewett Lee, a distant relative to Robert E. Lee and general counsel for the Illinois Central Railroad, when she was nineteen. The marriage produced three children, but ended in a long separation and eventual divorce in 1914. She never remarried.

As part of her early domestic education, Fanny learned to make miniatures; a hobby which seems to have taken a renewed hold on her after she was married and divorced.

Her first solo-built miniature was completed in 1913 as a birthday present to her mother. Lee recreated the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in exact detail. The model included ninety musicians, their instruments, sheet music, stands and accompanying instrument cases, among other minute details. She completed the model in two months. Later, she'd go on to famously to recreate the Flonzaley Quartet in miniature.3

Interest in Forensics

Her interest in crime began when she was forty-four. She became intrigued by the mysteries told by her brother’s good friend, George Burgess Magrath, a fellow student at Harvard and eventual medical examiner in Boston.4 He'd regale her with stories of the real-life crimes he helped solve.5

Through her friendship with Magrath, she learned the challenges of investigating violent deaths. Coroners were not required to have medical degrees and the police were not trained in how to gather and preserve medical evidence. As such, many murderers went free because of ignorance and poor training.6

After her parents died in the 1930s, she came into her inheritance and endowed a department of legal medicine at Harvard. She established the George Burgess Magrath Library of Legal Medicine and underwrote a chair for the department, a position first filled by her friend Magrath.7

By 1936, Harvard was well underway in graduating medical examiners. However, violent deaths were still going unsolved because law enforcement didn’t know how to handle or even identify pertinent medical evidence. Frances then inaugurated Harvard Seminars in Homicide Investigation (later renamed the Harvard Associates in Police Science seminars,) specifically tailored to the needs of law enforcement. She organized the week-long seminars and managed the curriculum, with the help of Harvard University and extensive specialized research in forensics.

Harvard Associates in Police Science

The first Harvard Associates in Police Science, or HAPS, seminar was held in 1945. Participants were invited from around the northeast and spent a week learning the art of crime scene detection.

She invited experts to attend and lecture on all matters pertinent to death investigation, including identifying the victims, determining time of death, the role that information played in an investigation, and interrogation techniques. Typically, twenty-five to thirty policemen of all ranks would be invited. Upon completion, each graduate became a memeber of HAPS and was then part of a larger network of investigators.

The week culmunated in a lavish banquet, often served on $8,000 dinnerware at the Ritz. The participants were wined and dine and often went away with a sense of camaraderie and a network of other highly-trained investigators on which they could call when presented with a difficult case.8

Even with the seminars, hands-on training for these police officers was impossible due to time constraints, privacy concerns and the unlikeliness that a violent crime occurring during the week-long seminar. These hurdles led Mrs. Lee to create crime scene models, a teaching tool she dubbed The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.10